How to Create Great Proposal Themes (Part 4): A Method for the Madness

- 1.How to Create Great Proposal Themes

- 2.What’s a Proposal Theme and Why is it Important? (Part 1)

- 3.How to Create Great Proposal Themes (Part 2): Features and Benefits

- 4.How to Create Great Proposal Themes (Part 3): The Proof is in the Pudding

- 5.How to Create Great Proposal Themes (Part 4): A Method for the Madness

- 6.How to Create Great Proposal Themes (Part 5): Who You Gonna Call?

- 7.Telling Your Story: Compliant and Compelling Proposal Themes that Win

The recipe for theme development includes a few simple ingredients from the RFP and the capture plan

In Part 3 of this series we described the importance of providing differentiating proof for features and benefits to substantiate your claims and to give your customers the reasons to believe. Part 4, introduces a proven methodology for developing winning proposal themes that are compliant, compelling, and position your company to win.

Proposal theme statements were formalized by a group of Hughes Aircraft (now Raytheon) engineers. These proposal pioneers were tired of a highly inefficient proposal development process, low win rates, and frustrated subject matter experts who were pressed into proposal writing duty. After some period of trial and error, they developed an appropriately named methodology called STOP. The Sequential Thematic Organization of Proposals (STOP Methodology) was released as a formal company manual in 1965 and ushered in the standardized use of what is commonly referred to as storyboarding.

The thesis statement (modern-day theme statement), the proposal outline, graphic concepts, and review sessions were the pillars of this methodology. The idea worked. Proposal development time was dramatically reduced. Subject matter experts were much more efficient. Win rates increased significantly. STOP was a success.

Over 40 years later, the original storyboarding pillars have been repackaged and rebranded but essentially remain the same. The Proposal Development Worksheet (ShipleyAssociates), the Module Specification, Storymap, and Annotated Mock-Up (SM&A), the Content Plan (CapturePlanning), work packages, and other proposal planning documents are all descendants of the original STOP storyboard concept. These modern-day proposal development tools all have the four STOP pillars in one form or another and emphasize the importance of thinking about (and writing down) proposal themes BEFORE proposal writing begins. Failing to follow this simple idea causes teams to fall into a number of common proposal development traps.

- Drafting proposal prose before themes are identified and vetted.

- Placing too much emphasis on the wrong features and benefits.

- Lacking a common vision and thematic threads throughout the proposal.

- Playing into the hands of your competition with a ‘me too’ response.

- Writing throw-away proposal drafts that significantly waste writer and review time.

What can proposal teams do to avoid these common pitfalls?

The Recipe for Success

There are a number of established ways to develop proposal themes and differentiators. The best recipes for theme development all have common elements that include a few simple ingredients that come from the RFP, the capture plan, and the collective intelligence of your capture and business development teams. Exact measurements may vary depending on the type and quality of the RFP.

- 2 ounces of proposal evaluation criteria

- 1 ounce of proposal instructions

- 4 scoops of solutions (one for each proposal volume)

- 2 dashes of customer hot buttons

- A pinch of competitive intelligence

Use a Method…Any Method

Although the proposal theme recipe sounds simple, most proposal themes end up being…well…half-baked. The problem is many proposal teams fail to invest the appropriate time and resources developing proposal solutions and themes. Many proposal teams bolt for the boilerplate and forget about themes altogetherhoping that they will miraculously emerge in the Executive Summary the night before the proposal is due.

There are scores of proposal development methodologies that include some form of theme development process. I recommend a simple 3-step process that starts with the RFP and applies basic capture information including customer hot buttons and competitive intelligence.

Example: The technical volume of a five-volume DoJ proposal is worth 60 percent of the points and the other four volumes are of equal weight (10 percent each). The technical section of the RFP and the capture plan contain the following relevant information:

Detailed Requirement (Section C): “Shall provide an automated tool for software development.”

Instructions (Section L): “Shall describe the tool and how it saves time and reduces cost.”

Evaluation Criteria (Section M): “Ability to meet or exceed service level agreements.” “The lowest risk scores the most points.”

Customer Hot Buttons: Proven software is key, especially on other DoJ projects. An easy to use intuitive graphical user interface is a must.

Competitive Intelligence: The incumbent contractor failed miserably in training DoJ programmers to use the tool effectively and efficiently.

The number of themes you develop should be roughly proportional with how the customer will weigh (and score) your proposal. For this example, consider 5-8 high-level technical themes and 1-2 themes for the other four volumes to represent the relative (6 to 1) ratio between the weighting of technical volume and the other volumes.

This approach obviously depends on the wording of the evaluation factors and the real weighting of the price factor. The main point is that placing too much emphasis on anything but the technical solution in this example is likely to yield a number of high-level themes that are not as important to the customer resulting in lower evaluation scores.

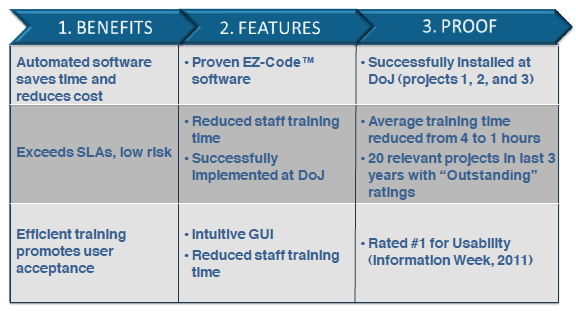

Step 1: Use a simple three-column table to identify major customer benefits (column 1) and your related solution features (column 2). Keep is simple by starting with 3-4 major customer benefits and 1-2 solution features for each benefit.

Step 2: Once the high-level features and benefits are developed, list the proof points (column 3) for each benefit. Define as many proof points for each theme as you can, using quantifiable metrics. Be creative, and get as many of your ideas down on paper. A good starting point is 4-6 proof points for each theme. Use the capture plan as the basis for integrating customer hot buttons and competitive information into the themes and

proof points to create powerful differentiators that truly differentiate.

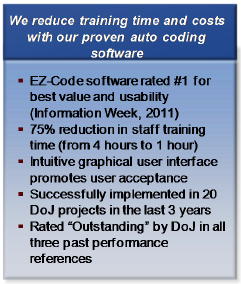

Step 3: Use a proposal template that highlights the theme statement (feature and benefit) using color, bolding, italics, or a combination of these to make the theme statement stand out. Pair up the supporting proof points in a focus box with each theme statement as shown.

Our EZ-Code™ auto-coding software reduces staff training time from 4 hours to 1 hour with an intuitive graphical user interface implemented on 20 DoJ projects.

Our EZ-Code™ auto-coding software reduces staff training time from 4 hours to 1 hour with an intuitive graphical user interface implemented on 20 DoJ projects.

Incorporate theme statements and focus boxes into the storyboard, module plan, content plan, or whatever pre-proposal planning deliverable you use. Develop a complete and sufficiently detailed compliant outline with proposal themes for each major section. Sketch out some graphics concepts to illustrate the major features, benefits, and proof points that are consistent with your theme statements and use graphic action captions to re-iterate the themes. Review the themes, outline, graphics, and action captions with your management team for validation, enhancement, and approval. Then, and only then, are you really ready to start writing the proposal.

Even the companies that have established proposal development organizations, processes, and tools in place often fail because they either lack the discipline to follow standard theme and proposal developments procedures or they simply don’t have the right people on the team.